ART AND HISTORY OF SYRACUSE

Syracuse experienced three distinct movements

of exceptional development in art and culture.

The first was the Greek era, when the city was a metropolis comprising hundreds of thousands of inhabitants and a fleet that sailed throughout the Mediterranean.

The second was the period of gothic art and the early renaissance, when it was the capital of the Camera Reginale ("Queen's Chamber"), a sort of personal fiefdom of the queens of the Kingdom of Sicily and Naples.

The third was the baroque period, when Syracuse had to be partially reconstructed after suffering damage from an earthquake in 1693.

A Large Greek Metropolis on the Mediterranean

Few recall that before the Roman conquest Syracuse was, for a long time, one of the grand metropolises of the Mediterranean and the only one able to fight the Carthaginians, defeat the fleet of the Etruscans, or engage in battle with the fleet of Athens, to the point of to suffering – and repelling! – a double attack (in 433 and 416 BC).

One is perhaps misled by the memory of Syracuse as it returned to being after the fall of the Roman Empire: a city of a certain political and cultural weight but restricted once again to the island of Ortigia where it originated. Instead, at the time of the “tyrants” (the somewhat flattering name by which the kings were called by their enemies), Syracuse had a footprint equal to that of today, as anyone traveling from Ortigia to the archeological area will notice.

Syracuse was the object of a careful plan of reconstruction and expansion (helped by the forced deportation of the populations from several defeated cities), evidence of which is still noticeable in many places.

Moreover, it says something that for the construction of the wall and fortifications, at a time of war against the Carthaginians for control over Sicily, Syracuse could mobilize as many as 60,000 men at a time, manage to build the ramparts in record time, and thus thwart the enemy attack.

Its extraordinary power and wealth made the ancient city a point of international attraction for the most famous Greek intellectuals. Among the illustrious names that stayed in Syracuse we find: Plato, Pindar, Aeschylus, Simonides, Bacchylides, Sofrone, Epicharmus…

Being familiar with these circumstances allows one to more easily understand the splendor and size of Syracuse’s monuments from the Greek period. Even if they were, unfortunately, half demolished in modern times to recover their stones, what remains is enough to rank them among the most important and beautiful that the Greeks had left in Italy, thus rendering Syracuse worthy of a leisurely visit.

A Middle Age not so Dark

|

| The palazzo della Camera Reginale |

Beyond this, it is worth noting how much remains of the gothic buildings constructed during the period in which Syracuse had the rank of capital of the Camera Reginale (1302-1537), among them the Palazzo della Camera Reginale itself (located a few meters from Piazza Archimede).

The Camera Reginale constitutes a sort

of “state within a state” and was formed from a fiefdom of a group of cities

from which revenues were used for the personal patrimony of the ruler of

the kingdom of Sicily and Naples. It was a sort of endowment given

to the bride by the groom himself, and passed down from queen consort to

queen consort.

The presence of Court fostered the rebirth

of a local political-bureaucratic class and left the city with an elegant

gothic imprint that bears the impression of local characteristics, which

owes much to the Catalan

gothic (less bound by the presence of the pointed arch, less

likely to feature soaring surfaces, much more sober, and favoring closed

and smooth surfaces than those that characterize the international

gothic style, especially “flaming”).

The relative decline caused by the suppression of the Camera Reginale would hold back further building, conserving the fundamental gothic and renaissance flavor of the city, until an earthquake intervened in the baroque period, forcing the rebuilding of a large part of Syracuse in the dominant style of the time.

Despite this, several very elegant buildings

that survived this and other earthquakes and are scattered throughout the

city can be admired even today.

Among these, the Palazzo

Bellomo (seat of the Galleria regionale), Palazzo

Mergulese Montalto, Porta

Marina, Palazzo Chiaramonte, the Maniace

Castle, the church

of San Martino, Palazzo Gargallo, and the church of San

Pietro al Carmine.

Jewels of the Baroque

|

| The courtyard of the Palazzo Bonanno, a beautiful example of the Syracuse baroque |

More than 45 villages were destroyed and resulted in approximately 60,000 deaths. Several towns were literally razed to the ground, as was the case with the not-so-distant Noto, which was reconstructed from the ground up, thus producing the “capital of the baroque” that everyone knows.

Even if, in the case of Syracuse, complete reconstruction from scratch was not necessary, the rebuilding resulted in a prevalently baroque style with just a few surviving gothic and renaissance monuments.

The local limestone, easy to work with,

allowed the stone cutters and the sculptors to indulge in those lacy stone

balconies and facades that the buildings display in abundance.

The local baroque style is lighter and

less elaborate than that,

equally known, of Lecce, and leads to an airier result.

But no less fanciful: no two baroque balconies are the same among

them and all compete in the pursuit of “invention” so dear to the baroque

aesthetic.

Given the sheer quantity, it is impossible

to list all of the baroque buildings of Syracuse.

One is advised to follow on foot the principal

streets of Ortigia (such as Via Vittorio Veneto – on which sits

the Algilà

Ortigia Charme Hotel – Via Maestranza, Via

Giudecca…) to discover the thousands of surprises of baroque

Syracuse.

Following the explosive building period of the baroque, the city would enter a period of economic and political stagnation up until the unification of Italy, when expansion began again reaching up to the borders of the Greek city, and in the end, overtaking them.

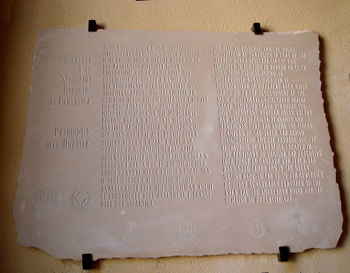

|

| Plaque at the Palazzo del Senato that records the proclamation of Syracuse as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. |

Those who visited the island of Ortigia 20 years ago will remember the abandoned condition in which it was found: the social changes of Italy after the war (the area of Syracuse saw in that period a significant process of industrialization), and emigration brought progressive depopulation to the island.

Emptied of its inhabitants (who moved to new and more spacious houses on the mainland), and no longer undergoing maintenance, Ortigia literally began to fall to pieces.

Fortunately, after the mobilization of

many people and associations who had fought a substantial battle to save

its heritage, the island in the last 15 years (in the meantime proclaimed

a World Heritage Site by UNESCO) was able to benefit from intervention

and financing.

With this triggered a beneficial wave

of restoration and redevelopment that has literally changed its face.

While it is true that one can still notice while walking around Ortigia buildings that are crumbling and propped up (albeit still beautiful), by now a large part of the island exhibits a new face, returned to its original splendor.

However, this phenomenon unfortunately also has its disadvantages. The decision to save all of the island at once has, in fact, resulted in delays and difficulties. Visitors can therefore find some of the monuments they had hoped to visit “closed for restoration”.

Fortunately, the wealth of history and art of Syracuse is such that despite le rinunce/the sacrifices, it would be difficult to see everything, and at least be consoled by the thought that the restoration work, in this case, was truly urgent and truly a “question of life or death.”

It is worth being patient in the face of a story that for once, after all, has a happy ending.

Back to TOURISM IN SYRACUSE, SICILY